The Little Engine That Could: A Tragedy

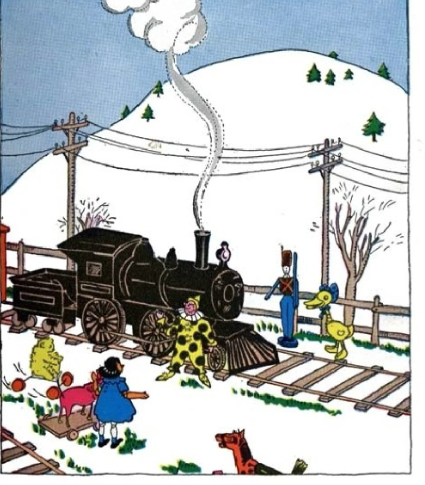

The Little Engine That Could is one of my favorite children's books. It is a straightforward, encouraging lesson drawn through a gently-paced narrative and digestible characters. Perhaps owing to its time where a plot indiscretion or two wouldn't raise an eyebrow, at the end of the story a sizable loose end, disappointingly, remains unresolved. But first a quick recap of how we get there. We'll start with the 1930 version by Watty Piper and illustrated by Lois Lenski.

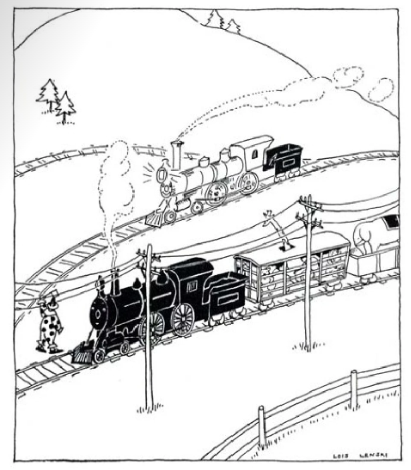

A significant and often overlooked section of the story (the bulk of the book, in fact) takes place before the eponymous train that could is even introduced. The first engine we meet is carrying all sorts of wonderful things for the good boys and girls on the other side of the mountain. "She puffed along merrily", we are told. Just as abruptly as this first engine is introduced, we are faced with the motivating problem that stretches over the remainder of the text. "...[A]ll of a sudden, she stopped with a jerk. She simply could not go another inch." Without warning or explanation, the first train comes to a halt. No one seems terribly curious about directly fixing whatever problem this first engine has, though there is some momentary anxiety about the good boys and girls who will presumably go without all the aforementioned good things to eat.

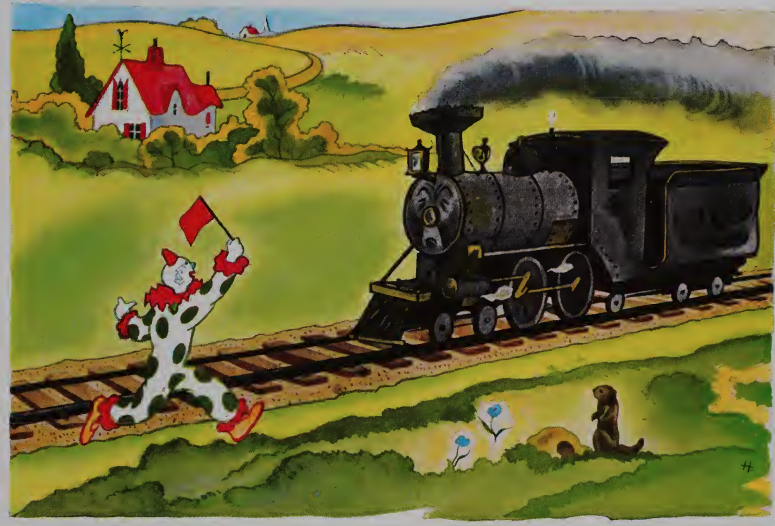

The Little Engine That Could moves at a swift pace. A passenger clown assumes command of our hapless crew and flags down a "shiny new engine" passing by, asking for help in completing their journey to the sympathetic boys and girls who await their goodies. From this point onward, the first engine is only referred to indirectly during the explanations the clown offers to passing trains. Building tension and despair, the shiny new engine dismissively refuses to get involved, as do several other engines for a variety of reasons.

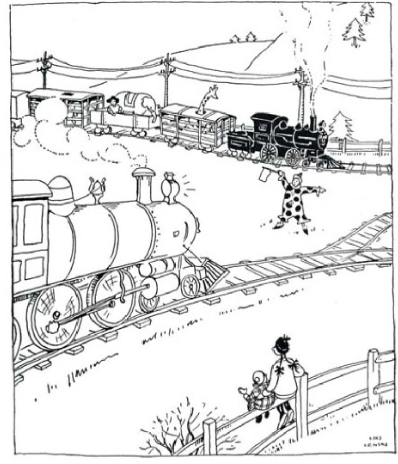

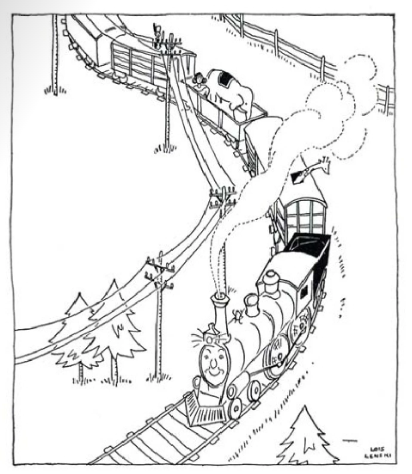

From the illustration of the encounter with the shiny new engine, we can see at least two tracks that meet, one for each of the engines mentioned so far. The first engine remains attached to the rest of the cars in front of the approaching new engine. Subsequent illustrations of the other engines who refuse to render aid show the broken engine attached to the main line of cars with the passing engine on the opposite track.

The penultimate engine rolling away offers a bit more detail to the scene.

Finally, our hero enters. The "Little Blue Engine" is small and inexperienced–she has never been over the mountain–but what she lacks in proven strength is more than made up for by a helpful attitude and a hopeful belief in her own potential. Like a good girl boss, the little blue engine is the only other explicitly feminine engine along with the first engine who broke down.

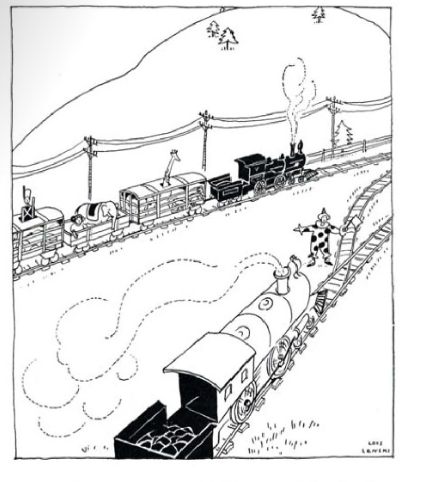

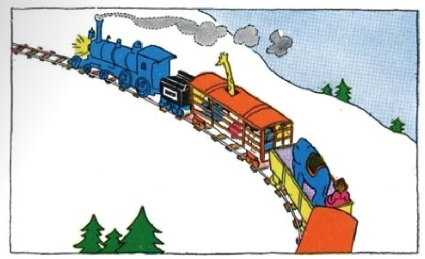

In keeping with established convention, the little blue engine appears from the side track, this time clearly turning to meet the stuck train.

The little blue engine agrees to help, hitches herself to the train, and pulls everyone over the mountain by way of sheer will power and repetitive affirmations.

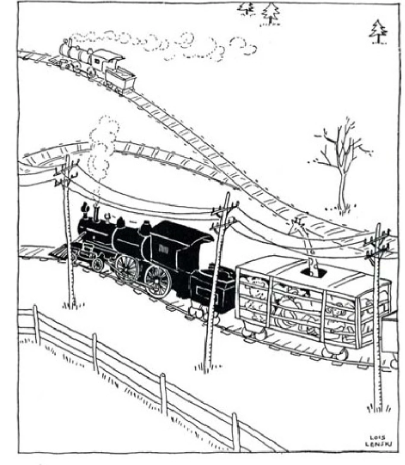

Notice anything curiously absent from that last image? Did everyone make it across the mountain? Let's check the final panel in the book.

Even in the more complete view of the heroic engine tugging our precious cargo, there is no trace whatsoever of the first engine. There's clearly only one possible scenario we can entertain: Those assholes just left her there. The little blue engine pulled herself ahead a ways on the track, the old broken engine was manually pushed over to the adjacent track before the blue engine hitches herself to the train, as we are told in the text. At that point, the broken engine is discarded from the story without a second thought. Charity compels me to consider the possibility that these details were simply omitted from the supplied illustrations out of carelessness. Fortunately, other versions of the story with fresh illustrations exist that can serve as a point of comparison.

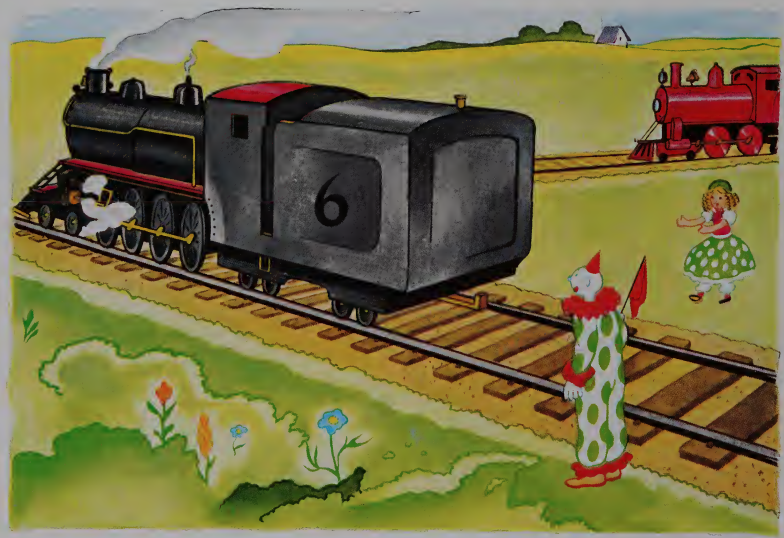

Here's a sample from the abridged edition of the Watty Piper version published in 1954, this time illustrated by George and Doris Hauman. This is the widely known version familiar to almost anyone who hears this story these days.

The composition of the scene is broadly similar to the earlier version with a more detailed rendering and better color. Most of the panels with the passing engines are close-ups featuring individual engines that don't provide much more information of the broader situation.

One major difference in the abridged version is an expanded sequence of panels featuring the little blue engine. Notably, the original broken engine is completely absent from the illustrations after the meeting of the penultimate train. We never see the two female engines together. Despite more than a few chances to include the first engine in the victory of the story, the illustrators chose to emphasize the heroic blue train. Even the triumphant frame showing the entire span of the train hitched to the new engine makes it clear the broken engine was not carried up the mountain and across the other side.

Despite the unmistakable influence of the original suite of panels, both versions stand on their own as original works. Across multiple illustrators working on different versions decades apart, the same damning conclusion is unavoidable: The abandonment of the broken train has been confirmed by tradition and can safely be viewed as a canon event.

We are plainly told that despite her best efforts, "her wheels would not turn". Without the strength of the determined blue engine, how will the stuck engine ever escape her plight? Repeated calls for assistance went unanswered until the final blue engine saved everyone else. What hope remains for a sole engine sitting on the tracks broken and unable to move on her own? It seems the price of the blue train's victory is the casual indifference to an engine who has nothing more to offer and has taken her cargo as far as she is able. The parable at the heart of the story celebrates effort and a confidence in one's own abilities, but what does that mean for a truly broken thing who has exhausted such potential?

And that's to say nothing of the desirous "good" boys and girls serving as the final end of all this suffering and struggle. Are they responsible for the sufferings of the cast aside engine who played every bit as critical a role in the delivery of their goods as the plucky little blue engine? I originally wanted to focus on that last question when thinking about this piece but it's probably best left as a separate follow-up, since I'll almost certainly drag in random bits of Kant and Hegel.

Hope that was enjoyable, and happy chugg chugging and puff puffing.